For anyone who hasn’t been to graduate school, it is a strange experience for three basic reasons. First, you are basically broke unless you are one of the intrepid individuals who decides to be burned out all the time by working and going to school. Second, you keep very odd hours. Third, you write things that no one in the real world would ever want to read.

For anyone who hasn’t been to graduate school, it is a strange experience for three basic reasons. First, you are basically broke unless you are one of the intrepid individuals who decides to be burned out all the time by working and going to school. Second, you keep very odd hours. Third, you write things that no one in the real world would ever want to read.

So, my friend Daniel K, a second-year law student at the University of Baltimore, and I send each other papers from time to time. At one point last year, he was working on something for a law review centered around Viacom v. YouTube. Since he fashions himself an expert on such things, I decided to bring him in on Zuffa’s case against Justin.TV.

Mann Talk: We talked a bit about the similarity between Zuffa’s case and Viacom v. YouTube when you picked me up at the airport that time. Are the two really that similar, or were you just mouthing off because I made you pick me up?

Daniel K: This case is identical to the facts in Viacom v. YouTube, in fact Zuffa filed amicus briefs in Viacom arguing for a tougher approach to this issue of Digital Millenium Copyright Act (DMCA) Take Down notices, and when the court held for Viacom, Zuffa must have decided that to go forward was worth the costs of litigation.

All the copyright law that deals with user uploaded streaming content comes from the DMCA, which was passed long before behemoths like YouTube or Justin.TV. It was mostly a way to control the content on webhosted sites (remember when every jerkoff had his own website complete with dancing GIFs and embedded music?)

The takedown notices work like this. User uploads infringing content. Copyright holder sees the infringement, and writes a letter to the Internet Service Provider. This is a real letter (not an email) complete with names, name of the content, URL of the content, person to contact for more information, and an official signature. Keep in mind that this letter must be written each and every time the ISP finds content that it wants removed from the site.

The ISP then gives notice to the user, who has an opportunity to insist that he is free to upload the content. 9 times out of 10 he is not free to do so, and so the content gets stripped. But the user suffers no repercussion. If he uploads infringing content onto the site later that day the whole process begins again.

This won’t last forever. Public policy will eventually dictate that we give copyright holders more protection. YouTube was actually the lucky one because those guys made millions and millions basically off of pirated content, then sold the business to Google before the party crashed. So last year we had Viacom and this year we will have a Zuffa holding, and the DMCA will get chipped away until Congress abrogates it. The real question is what people are proposing for the future take-down requirements.

Mann Talk: You say “the court held for Viacom.” What was the ruling? Can courts enforce stricter regulations?

Daniel K: Last year, Viacom v. YouTube was a big decision on the rights of copyright holders against Online Service Providers (OSPs) that post their content. In that case, Viacom sought damages for infringing content (music videos, film and TV clips) that users had uploaded onto YouTube. The court held that YouTube was protected by a “safe harbor” statute because they complied with the take-down procedures laid out by Congress. Although YouTube escaped liability this case opened the door for future OSPs (like Justin.tv) to be found liable whenever they are not in full compliance with the take-down proceedings.

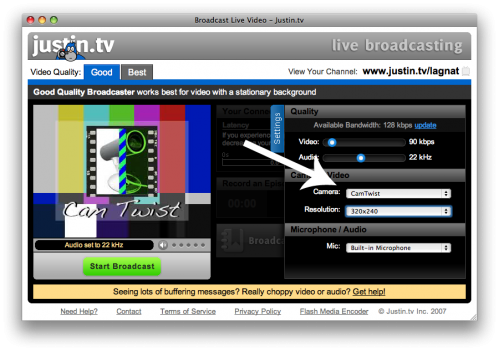

Zuffa is alleging that Justin.tv has induced infringement from its users, and has not cooperated with Zuffa in finding and removing the copyrighted content. There is no doubt that Zuffa waited to hear the summary judgment in Viacom v. YouTube so as to effectively distinguish that case from their own. I imagine that Zuffa will try to argue that Justin.TV relies upon uploading copyrighted content as their chief source of income and popularity. This would distinguish Justin.TV from YouTube because YouTube was able to convince the court that copyright infringement was merely a side effect for other applications. The fact that Justin.TV streams content to its website rather than uploading videos could potentially be big, since streaming allows for a live feed on sporting events like UFC events—in other words it is an application that is highly likely to infringe.

On the other hand Justin.TV will try to argue that it qualifies under “safe harbor” for the same reasons that YouTube did. They will highlight their cooperation with Zuffa on finding infringements, and their other useful applications as an OSP.

Mann Talk: Are individual Justin.TV users in danger?

Daniel K: No. In previous cases Zuffa has tried to go after individual users, but Justin.TV correctly refused to give up their names. This case is entirely about JustinTV’s responsibility as the inducer of infringement that users commit. Copyright holders are increasingly adamant about punishing users for their infringing uploads, but that is simply not how the statute is written. But don’t think for a second that this is so out of some kind of sympathy for the users. It is a purely practical concern. There are too many infringing users to litigate, the users don’t have nearly enough money to satisfy damages, and it simply makes more sense to go after the OSP since they provide the platform upon which the infringement is possible in the first place. This country has always protected the property interests of copyright holders, and copyright law does not discriminate between infringement via computer upload then from any other kind. But in the information era it has just gotten harder to go after infringers because they have safety in their numbers. But my prediction is that eventually the law will catch up.

Mann Talk: What is Zuffa trying to accomplish? Are lawsuits like this at least partially public relations moves for future public policy decision?

Daniel K: Absolutely. Zuffa is at least in part lobbying for a change in copyright enforcement. This issue stands at a crossroads in copyright law. It is hard to argue that a copyright holder does not have the right to protect his creative works. If the UFC could not generate revenue from their matches there would be no UFC. When the copyright law was first written 100 years ago things were a little simpler: you wrote a book and if someone made illegal copies of your book you could enjoin him.

With user-uploaded live streaming on the internet the copyright law gets more challenging to enforce. Zuffa wants to see tougher enforcement mechanisms against OSPs like Justin.TV. In their amicus brief during the YouTube case, Zuffa wrote specifically that the safe harbor provision should be construed more narrowly and that copyright holders should have a fuller arsenal to protect their content. This is a message to Congress as much as to the court. Whenever litigation crops up on a particular issue like this it is generally a sign that the legislation is outdated and it is time for Congress to revisit that issue. Keep in mind that the safe harbor provision first went into effect in 1998. Remember what the internet looked like in 1998?

It looked like dog shit.

Mann Talk: Anything else you want to add here?

Kamenetz: Yeah, if any of your readers are Justin.TV users they should know that nothing I say disclaims the fact that they could be totally [in trouble] somehow

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by Travis Walker and MMA Headliner, MMAFightForce. MMAFightForce said: @mmafightforce Mann Talk – Taking a closer look at Zuffa vs. Justin.tv with my future defense… http://goo.gl/fb/HA4rc […]